thabir – Interruptions

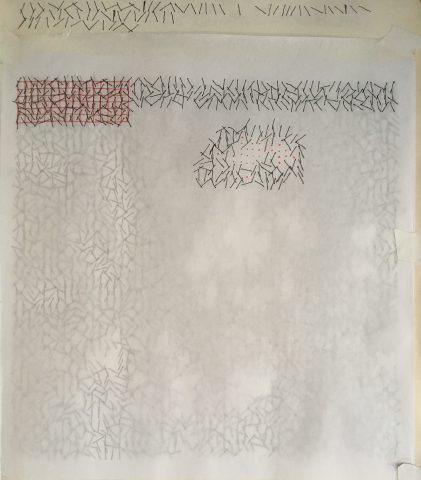

I began by studying the work. I found the most effective method for this to be copying/tracing the work into my notebook, which is what I started doing:

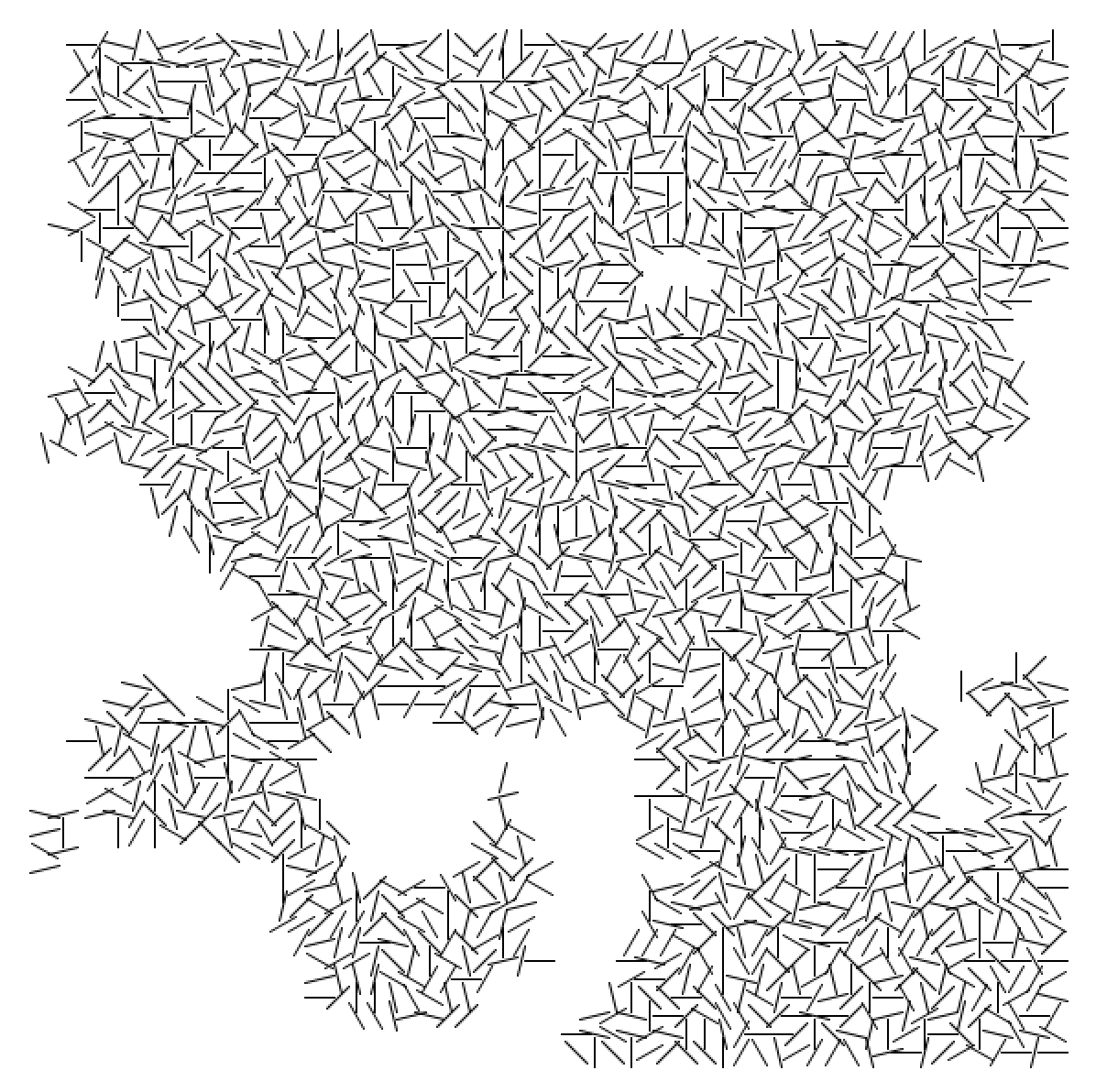

- The artwork is square with equal margins on all side

- The artwork consists of many short black lines of the same length and line weight

- The centers of these lines form a grid, indicated by the red lines in the top right hand corner

- The lines are place at angles between +90 and -90 degrees

- Not all angles seem to be represented. Certain angles get repeated quite frequently and there are certain repeating patterns/units/motifs as well

- However, within a smaller subset of this angle range, the angles seem to be randomly chosen, for some definition of random

- Interspersed throughout the grid are spots where the grid is empty or ‘interrupted’

- These spots do not seem to have a set shape, size, or placement. All these features seem to be random

- Spots on the grid which have a greater number of empty neighbors seem to have a higher probability of being empty.

I found this assignment to be particularly interesting because of the simplicity of the results we were trying to reverse engineer. This simplicity allowed us to focus on the expressive and poetic qualities of the generative art experience as opposed to the purely technical aspects. Because we weren’t bogged down with the weight of libraries and sensors, we could focus on the subtle variations in effect of lines, probability distributions, and randomization, rather than wracking our brains trying to get our code to compile.

This aspect of the assignment showed me how there was nuance in code, how two different solutions could technically satisfy all of the bullet points I listed above, and yet could both fall short in surprisingly different ways. It started getting me thinking about code experientially.

I found that the hardest part was achieving the effect of the line angles and interrupted spaces. Getting the line placement was easy enough after sketching for a bit, because I noticed the lines were on a grid. However, the angle distribution was trickier. I ended up reducing the possible angles that a line could take to a small set and used a probability distribution on that set to generate angled lines. I also used a probability distribution on a cell’s surrounding cells to decide whether it would be interrupted or not. A greater number of surrounding interruptions causes the probability of interruption to be higher. This is basically a probabilistic cellular automata. I had to go through a couple of iterations before I could be satisfied with my results. Before I used the cellular automata method, I tried using Perlin noise but that wasn’t as effective as I hoped. An image from that iteration is attached below.

I think what I really learnt was that this form of coding is just like drawing, in that it is all about the interaction of the image with the eyes. The “correctness” of the code itself is absolutely irrelevant to the final effect, and therefore it is a matter of iteration and refinement to achieve what you intend.